by Dmitry Klokov, Snejana Hill

Spoiler alert – it is very important. And not only to skin function and health, but also to our health in general. Even more so, as results of recent research suggest, the microbes that inhabit our skin may even affect our mental states [1].

But first things first. The skin microbiome – the community of all the microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, and other more exotic and rare types) that live on and inside our skin – is an integral and indispensable part of our organisms. Note that the skin microbiome is part of the human microbiome – the totality of all microbes that colonize the gut, lung, mouth, uterus, vagina, and other anatomical sites.

In fact, a human body contains more bacterial cells than own human cells! [2]

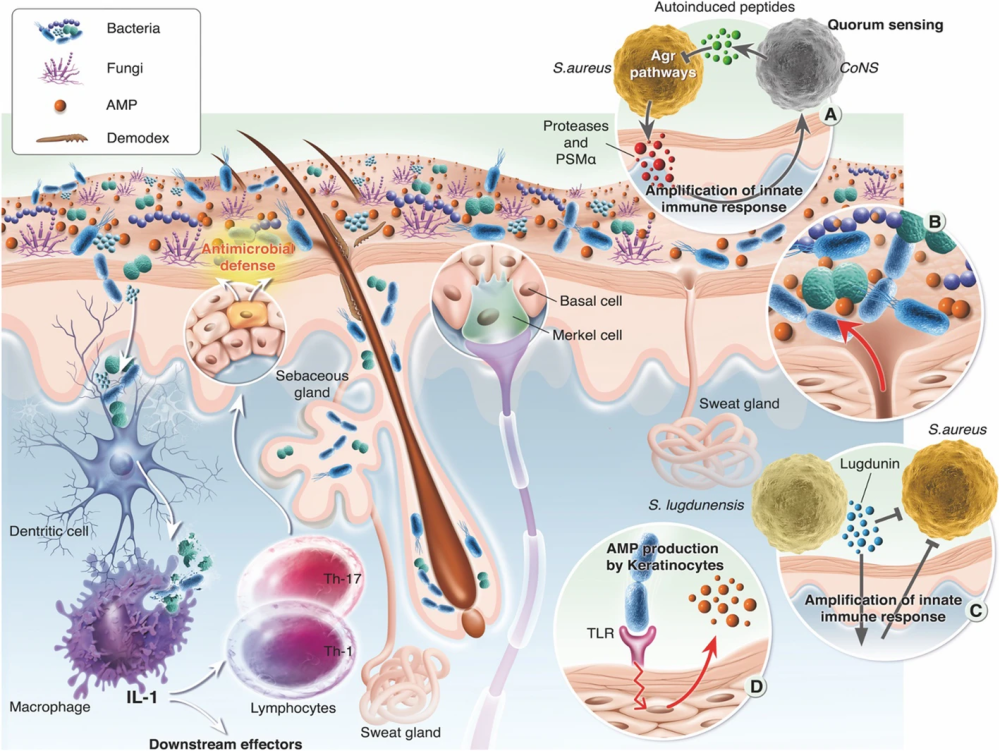

This community is very diverse consisting of thousands of different species [3]. It is the composition of the microbiome – the roster of species and their relative numbers – that defines whether things go well or not so well [4]. During the millions of years of coevolution, we adjusted to each other and learnt not only how not to harm, but also how to gain benefits from each other’s presence. The benefits that a proper skin microbiome provides to us are numerous. In infants, “good” skin microbes help build healthy skin and train the immune system [5]. Healthy skin consists of three major layers – the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis – and each of them has a very complex architecture and composition. The main function of the skin is a barrier function – not to let in pathogenic substances and microorganisms from the environment and to prevent the loss of moisture from the deeper skin layers. But don’t think of it as a passive physical barrier, which is a common stereotype, especially when it comes to the outermost layer of the skin called stratum corneum consisting of dead skin cells glued together by a complex mixture of biomolecules. Of course, the stratum corneum makes it very difficult for pathogens, such as “bad” pathogenic bacteria, toxic particulate materials, micro-parasites, viruses, to penetrate the skin. Of course, it protects the deep skin layers from the damaging effects of UV rays. But that is not all.

Even this “dead” layer of skin, where the majority of our “good” microbes live, is biologically active and most of its activity is exerted by these microbes [1].

For example, Staphylococcus epidermidis, which is one of the most common bacteria of the skin, helps to fight against the pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus [6, 7]. In fact, these Staphylococcus epidermidis bugs are our real friends. They communicate with our skin cells to help them produce the building materials for the lipid bilayer of the skin [8]. When you scratch or cut your skin, immune cells rush into the wound and cause inflammation (redness and swelling) – a good thing to have because they fight the army of not-welcome microbes. But the wound would not heal if the inflammation is not controlled and suppressed. It is Staphylococcus aureus that touch the right skin cells and “tell” them to stop sending proinflammatory signals [9]. Even more amazingly, Staphylococcus epidermidis can communicate with macrophages – our immune cells that travel in many parts of our body and fix all kinds of problems [1]. This means the skin bacteria can tune up our systemic immune function and improve states in other organs and tissues.

Scientists have noticed that people with an altered composition of the skin microbiome – the state called dysbiosis – are more likely to suffer from immunological diseases, such as asthma or allergies [1].

Not surprisingly, skin dysbiosis is found in many inflammatory skin conditions, such as atopic dermatitis, rosacea, acne and others [1, 3, 10].

Although these pathologies reveal themselves on the skin, their causes are deeply rooted in the malfunction of the systemic immune responses and changes in the way our cells work. Our metabolism is a myriad of biochemical reactions that help digest food and make biomolecules needed for normal cell and organ functions. If something goes wrong with it, say cells are forced to deal with excessive amounts of sugar, this affects our microbial friends everywhere – in the gut, in the lung and on the skin. “Good” microbes may succumb to “bad” ones, or they can turn into bad ones themselves. In one of the most common skin conditions, acne vulgaris, the bacteria Propionibacterium acnes which is present in large quantities on the skin of all perfectly healthy people [11], switches to a pathogenic mode – they become irresponsible commune members polluting their environment and causing inflammation [12]. Researchers think that this transition of Propionibacterium acnes from a friend to a foe is due to systemic causes associated with western lifestyle [3].

And what is the most prominent feature of the urbanized western society compared to rural traditional societies, except for diet? Correct, the cleanliness! In scientific terms, cleanliness means low biodiversity of microorganisms – in our homes, offices, city streets and shops. How does that matter? It matters big time. Researchers have found that the skin microbiomes – and the gut microbiomes too – of people from traditional farming communities are richer and more diverse than those of people from cities [13]. Those farmers – with good microbiomes – are less likely to get asthma, rosacea, allergies [8]. Those people almost never suffer from acne, but can get it when they relocate to the cities [14]. Not enough evidence to support the link between the microbial biodiversity in the environment to the skin microbiome and further to health? Then check a recent PhD thesis defended at University of Sheffield centered around the Environment-Microbiome-Health axis [15].

OK, the skin microbiome is important, and it is not in a perfect shape when it comes to city dwellers, like us. What should we do and how can we improve it? Just like we, humans, need good air, water, food, temperature and humidity, our bacterial friends on the skin need certain physical conditions. Good thing is that millions of years of coevolution ensured that our organisms naturally create these good conditions on the skin for the “good” microbes. Bad thing is our modern lifestyles make it very difficult for our bodies to do their jobs well. Stress, junk food, the lack of physical activity and the lack of contact with the biodiverse environment – all contribute to worsening of the skin ecosystem. It is not a brainer then – we need to approach the problem systematically. Thoughtful and well-balanced skin care is a good start. High quality cosmetics can provide skin with proper pH, moisture level, nutrition, biologically active components and photoprotection. Recent advances in the science of the skin microbiome – most summarized in this article – sparked the use of prebiotics, probiotics and postbiotics in skin care products. Substances isolated from “good” bacteria, for example, Bifidobacterium longum, can improve the skin ecosystem by both stimulating the growth of good microbes and improving immune communication in the skin [16, 17]. Live bacteria Lactobacillus reuteri (a probiotic), when applied to the skin, can improve inflammatory skin disease [18]. But be warned – because the use of probiotics in cosmetics is a very new trend, it is poorly regulated, leaving room for irresponsible use, misleading terminology, and unsupported claims from manufacturers.

Next comes the environment – as arguably one of the biggest factors contributing to the healthy skin microbiome [1].

A new concept of nature relatedness, which unites a system of views and lifestyle choices, refers to an individual’s affinity with the natural environment [1]. High level of nature relatedness not only would ensure contact with the environmental microbes – to enrich and support an individual’s own microbiomes – but would also support healthy mental states and alleviate stress. Research has shown that this can trigger physiological changes that are beneficial for our good microbes. And our alleviated microbiomes would in turn improve the skin function, immune defenses, and systemic health. The circle closed.

Luckily, to be able to benefit from the environmental microbiota, you don’t have to sell your city apartment and move to live on a farm. Even a short contact with soil and plants can make your skin microbial community healthier [19]. Time to start a balcony garden? Or take a walk in a city park or a green zone – even a single walk will improve your skin microbiome [20]. Get a dog or cat – through contact with pets we can diversify our skin microbiomes and directly or indirectly improve health [21].

The science of human skin microbiome is in its infancy and many “hows” remain unanswered. Yet, there is no doubt that our “good” microbes are deeply involved in the skin function which goes beyond local skin matters and helps to put in order many other parts of our bodies – mainly through interaction with the immune system. We should pay very close attention to our friendly skin bugs and help them cope with the hurdles that our urbanized lives bring them. This help should start with local skin care, but most importantly should take the form of a holistic approach where contact with the environment and healthy lifestyle play key roles. As we can see, a healthy microbiome of our hands is in our hands.

Copyright Snejana Hill Cosmetics. Use of this text or parts of this text without prior written permission from Snejana Hill Cosmetics is prohibited.

Cited Literature

- Prescott, S.L., et al., The skin microbiome: impact of modern environments on skin ecology, barrier integrity, and systemic immune programming. World Allergy Organ J, 2017. 10(1): p. 29.

- Sender, R., S. Fuchs, and R. Milo, Are We Really Vastly Outnumbered? Revisiting the Ratio of Bacterial to Host Cells in Humans. Cell, 2016. 164(3): p. 337-40.

- Byrd, A.L., Y. Belkaid, and J.A. Segre, The human skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2018. 16(3): p. 143-155.

- Grice, E.A., et al., Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science, 2009. 324(5931): p. 1190-2.

- Dhariwala, M.O. and T.C. Scharschmidt, Baby’s skin bacteria: first impressions are long-lasting. Trends Immunol, 2021. 42(12): p. 1088-1099.

- Baviera, G., et al., Microbiota in healthy skin and in atopic eczema. Biomed Res Int, 2014. 2014: p. 436921.

- Iwase, T., et al., Staphylococcus epidermidis Esp inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and nasal colonization. Nature, 2010. 465(7296): p. 346-9.

- Skowron, K., et al., Human Skin Microbiome: Impact of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors on Skin Microbiota. Microorganisms, 2021. 9(3).

- Lai, Y., et al., Commensal bacteria regulate Toll-like receptor 3-dependent inflammation after skin injury. Nature Medicine, 2009. 15(12): p. 1377-82.

- Stehlikova, Z., et al., Dysbiosis of Skin Microbiota in Psoriatic Patients: Co-occurrence of Fungal and Bacterial Communities. Front Microbiol, 2019. 10: p. 438.

- Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature, 2012. 486(7402): p. 207-14.

- Tomida, S., et al., Pan-genome and comparative genome analyses of propionibacterium acnes reveal its genomic diversity in the healthy and diseased human skin microbiome. mBio, 2013. 4(3): p. e00003-13.

- McCall, L.I., et al., Home chemical and microbial transitions across urbanization. Nat Microbiol, 2020. 5(1): p. 108-115.

- Cunlife, W.J., Cotterill, J.A. The acnes: clinical features, pathogenesis and treatment. In: Major Problems in Dermatology. vol. 6. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1975.

- Robinson, Jake M. (2021) Nature-based Interventions and the Environment-Microbiome-Health Axis. PhD Thesis, Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Sheffield, UK: link

- Baquerizo Nole, K.L., E. Yim, and J.E. Keri, Probiotics and prebiotics in dermatology. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 2014. 71(4): p. 814-21.

- Gueniche, A., et al., Bifidobacterium longum lysate, a new ingredient for reactive skin. Exp Dermatol, 2010. 19(8): p. e1-8.

- Butler, E., C. Lundqvist, and J. Axelsson, Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 as a Novel Topical Cosmetic Ingredient: A Proof of Concept Clinical Study in Adults with Atopic Dermatitis. Microorganisms, 2020. 8(7).

- Gronroos, M., et al., Short-term direct contact with soil and plant materials leads to an immediate increase in diversity of skin microbiota. Microbiologyopen, 2019. 8(3): p. e00645.

- Selway, C.A., et al., Transfer of environmental microbes to the skin and respiratory tract of humans after urban green space exposure. Environ Int, 2020. 145: p. 106084.

- Haahtela, T., et al., The biodiversity hypothesis and allergic disease: world allergy organization position statement. World Allergy Organ J, 2013. 6(1): p. 3.

Image from Boxberger, M., Cenizo, V., Cassir, N. et al. Challenges in exploring and manipulating the human skin microbiome. Microbiome 9, 125 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-021-01062-5